On Resistance

Before turning out the light last night, I emailed each of the ICE, DEI and Doge tip (snitch) sites* with a subject line “HOT TIP!!!” and taunting text that began “Hey there Toady....” The emails were signed “A Retired Civil Servant.” It lightened my mood and also evoked a memory that is dear to me and helps keep me buoyant when the weight of the assaults on our Democracy pulls me down. I want to share the memory but first give some context.

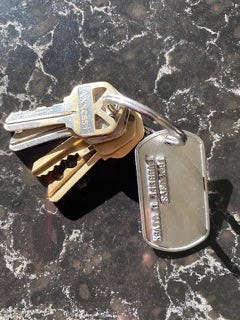

I retired from the Department of Veterans Affairs in 2015. It was time to leave, but it was hard because every two weeks I met with a dwindling group of former prisoners of war (POWs). I felt like I was abandoning them. They’re all gone and I think of them often. I carry the dog tags of the group’s unofficial leader, Darrell, on my key ring. Darrell’s granddaughter, Amy, gave me the copy of Darrell’s dog tags after he died in 2016. Amy, her father Butch and I started a scholarship in his name for veterans at a local community college.

I inherited the group after becoming “POW Veterans Outreach Coordinator” when the original Coordinator retired around 2002. There were 16 group members when I started: 3 POWs of the Japanese, 1 North Korean POW and the rest German POWs. Most of the German POWs were airmen who ejected from bombers and were captured by SS before German citizens could kill them. They were heavily interrogated by the Germans seeking any information about the Allied air campaign and were imprisoned with airmen from other Allied nations, mostly British. One airman (who later became a CT state senator) was shot down over the Zuiderzee, picked up by a Dutchman in a rowboat and moved around from house to house in a Dutch village before the resistance managed to get him to Brussels where he was, unfortunately, fingered getting off a train. Another Army Infantry member was captured by the Germans, liberated in time to return stateside and be assigned to “guard” German POWs being held on a farm in upstate NY (The prisoners played cards, cooked and were free to walk into town). The North Korean and Japanese POWs endured the most brutal treatment.

The psychological needs of former POWs weren’t understood or addressed until the1980s. In 1984-85, the VA invited all former POWs to complete comprehensive questionnaires that focused on mental health symptoms along with psychiatric evaluations for those that agreed. The release of the 52 American hostages from Iran on January 20, 1981 after 444 days of captivity in the U.S. Embassy in Tehran at the hands of pro-Ayatollah Khomeini students raised awareness of the psychological harm to those who endure such brutal, prolonged captivity. The “Iran Hostage Crisis” was the catalyst for the VA reaching out to former POWs. Not surprisingly, the POWs needed long overdue support and services including financial compensation for service-related disabilities and individual and group psychotherapy.

Darrell was one of the original group members. He enlisted in the Army to “get 3 hots and a cot” and send money home to a large family in Oklahoma during the Depression. He was stationed in the Philippines when the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor.

About 6 months after the inception of the group, a new member, Everett, walked into the room. He and Darrell recognized each other immediately even though they last saw one another in 1942, almost 60 years earlier. They met during the Bataan Death March following surrender for “humanitarian reasons” of tens of thousands of American and Filipino troops who ran out of ammunition, food and water following protracted fighting. They were like brothers if not twins who sat together, knees touching, at each meeting.

The group members talked for the first time in their lives about their experiences as POWs, how they survived and kept their humanity, their nightmares, drinking or working excessively to avoid remembering and feeling, helping each other through feelings of regret and survivor guilt. They also talked about everything else – growing up, the Depression, their families, careers. The group was sometimes subdued, often animated. They managed to get to the VA regardless of the weather. When one of them was late, they took flak. “Where the hell have you been?” was frequently answered with a corkscrew-like upward twist of the index finger signifying a prostate exam to a collective groan. They had debates and differences but were also loving and tender with each other. I got to know their wives and some of their children and grandchildren. They trusted me and let me in and I know I’m a better person because of them.

One especially lively meeting started when an airman recounted being interrogated by a German officer who spoke english and watched “too many” American movies. The airman weaved a fantastic tale about bootlegging as a gangster in Chicago, holding up trains with Jesse James, and after the man caught on, culminated in telling the officer to “eat shit.” It was worth the beating he took. They continued sharing stories of resistance and the energy in the room was electric. Another airman talked about scavenging parts with others in his “Stalag Luft” camp (for Allied airmen) in an attempt to construct a rudimentary radio, never producing a working radio but succeeding in the act of resistance alone.

Darrell and Everett had each been on multiple “hell ships” (in which POWs were transported around Asia as slave laborers, hundreds crammed into the bowels of ships in the dark for weeks with only brief glimpses of light and fresh air when the hold opened to lower food and water and empty “honey buckets”). Being caught in any act of resistance against the Japanese resulted in execution on the spot. Everett and others were forced to lay tarmac for Japanese landing strips. When guards weren’t looking, they peed in the tarmac to weaken it. They also honed the art of “slow walking” work while giving the appearance of working hard. Darrell was a slave laborer at a smelting plant in Japan, part of the manufacturing process for Japanese weapons. They added “anything we could find and get away with” to the machinery to gum up the works.

Individual acts of resistance are monuments of human courage, but it’s the added component of social networks that makes it (us) so powerful. Former POW Admiral Robert Shumaker who spent eight years in North Vietnamese prisons and who coined the term “Hanoi Hilton,” knew this. He helped create the “Tap Code,” an ingenious method by which POWs isolated in adjoining dank rat-infested cells could communicate with each other. In interviews with Shumaker years later, he talked about the Tap Code as an essential tool not only for “passing on information and organizing resistance, but also for preserving sanity” through collective action.

What felt so good about emailing the snitch sites was knowing that thousands of other citizens nationwide did the same thing (often with huge attachments) and collectively managed to overload the sites.

Notes:

*List of Agencies & emails:

· Where to report DEI contractors – DEIAtruth@opm.gov

· Where to report undocumented people - ICEOPRIntake@ice.DHS.gov

· DOGE Recommendations - Doge@mail.house.gov

From Chop Wood, Carry Water, Jessica Craven 1/27/25

Southwick SM, Charney DS. Resilience: The Science of Mastering Life’s Greatest Challenges. (2nd ed. Cambridge University Press; 2018), pp. 136-139

What inspiring stories and lessons we can learn about courage and resistance from these POWs. I’m glad they had a forum with you for support and healing through sharing and community. We should remember their bravery in these times as they were also fighting against fascism.